A major challenge facing educators is how to adapt courses to meet the learning neeeds of today’s students. NIU’s gen ed (general education) courses present a particular opportunity because of the desire to offer an introduction for students who may or may not be familiar with the subject while still being stimulating and compelling.

In recent years, two of the most popular gen ed offerings in the College of Visual and Performing Arts, ARTH 282 – Introduction to World Art and THEA 203 – Introduction to Theatre were redesigned to be more inclusive and better serve the learning styles of today’s students while still maintaining academic integrity.

The results have been impressive, and show that students are more engaged and perform better in both courses.

Three faculty members who played key roles in the redesigns recently discussed what factored into the decisions they made to breathe new life into their courses.

Gibson Cima, assistant professor of theatre and head of theatre studies

I was taught a certain way of thinking about theater history that was based on a set of assumptions that were geared towards the idea of White supremacy, of focusing on the work of White male “geniuses” who all were completely out of their time period and made work that was universal and could always be interpreted and spoke to everyone simultaneously. And, none of that is true.

I was taught a certain way of thinking about theater history that was based on a set of assumptions that were geared towards the idea of White supremacy, of focusing on the work of White male “geniuses” who all were completely out of their time period and made work that was universal and could always be interpreted and spoke to everyone simultaneously. And, none of that is true.

They don’t emerge fully formed from Zeus’s head. They are thinkers working within their own historical context and maybe their work isn’t what’s important for students today to know about.

For me, it was about what do [the students] need to know to understand theater, to become lifelong theater lovers, to understand how theater functions and what it can do and what it can’t do, what it does well and what it doesn’t do very well.

What can I let go of? The things that meant something to me in my education? Now I’m looking at them differently and saying maybe this isn’t the most important thing for these students to understand. It was a painful process of letting go of my education and starting anew and thinking, how can I create something that isn’t going to be an easy A, but that will be engaging for the students?

Periodization had to go away because it created that idea of a single narrative sweep of one thing leading to the next thing, leading to the next thing ultimately creating this porch of civilization passed through the generations, whereas that’s not really what theater is.

Ann van Dijk, associate professor of art history

One thing that makes ARTH 282 unique is that it’s a team-taught course. It’s divided into four units with different professors determining the content of each unit.

One thing that makes ARTH 282 unique is that it’s a team-taught course. It’s divided into four units with different professors determining the content of each unit.

We have thought about the overarching sweep of the course, but within each unit we’re each doing our own thing.

Mary Quinlan, professor of art history

In some ways we did not start with a blank slate, not so much because of it being team-taught; (and it used to be seven of us each teachingour research specialiteis), but because first of all, it is global arts to begin with. It never really quite that same thing about White supremacy. Back in the ’70s there was a revolt within art history against that. We’re talking about maybe 50 years of revolt against the old way to teach it, where it was literally a development of style that crescendoed from Greco-Roman through the Renaissance to Jackson Pollock, this sweep that really just told White men’s history. We actually never had that.

In some ways we did not start with a blank slate, not so much because of it being team-taught; (and it used to be seven of us each teachingour research specialiteis), but because first of all, it is global arts to begin with. It never really quite that same thing about White supremacy. Back in the ’70s there was a revolt within art history against that. We’re talking about maybe 50 years of revolt against the old way to teach it, where it was literally a development of style that crescendoed from Greco-Roman through the Renaissance to Jackson Pollock, this sweep that really just told White men’s history. We actually never had that.

When I taught ARTH 282 in 1996 or 1997, I was teaching Asian art history for two weeks, Muslim art for two weeks, African for two weeks and so on. In each of those I began with the religious traditions of the ones that Helen [Nagata, associate professor of art history] does much better now, but the Confucian tradition, the Taoist tradition, the Buddhist tradition, because how else could you understand those arts if you didn’t know those? I love Muslim art. So, of course the classes had to learn certain traditions of the Koran and the Hadith. Art history was always different.

Gibson Cima

Some of those disciplinary things in theater took longer to happen. We’re not talking about the ’70s, they’re talking more about the ’80s and ’90s. Up until when I was training, there was still that feeling of this is the Western arc and this is what is important to teach. Part of the process of redesigning the course was looking at the content of the course and saying, “We know what we mean when we say ‘World Music’ or ‘World Art,’ but what do we mean when we say ‘World Theater’?” How can I teach all of these different kinds of cultures in a way that doesn’t privilege Western European art?

Mary Quinlan

Of course, Gibson, you have a certain issue that we don’t quite have in the same way at all, which is when you’re talking about theater, you’re going to be talking about language, English language, and there is no language barrier in the visual arts. We have a language barrier for the kinds of evidence around it oftentimes. So, Jeff Kowalski [distinguished professor emeritus in art history] taught the arts of Mexico, Yucatan, Maya, Aztec, the Pacific Rim. We always had a very global approach that really wasn’t so shackled to English.

Gibson Cima

Whereas, I am often teaching in English translation, unless the play was written originally in English. Sometimes, even when the play is written in English, it’s old English and so we read it in translation.

Ann van Dijk

It’s worth noting that we always had quite a broad variety of faculty members, who covered a broad variety of topics from different parts of the world. I’m the medievalist, and traditionally medieval meant Europe and Christian. When we first started team-teaching my unit was European and Christian, and at one point I couldn’t live with that anymore and redesigned the unit. This was a number of years ago and now it has an almost equal emphasis on Christian, Jewish and Islamic traditions in that time period between the fourth century and the 15th century.

Gibson Cima

This is my first tenure track job—but before I came to NIU, I spent five years in one-year positions. I would be handed, “Here’s the Western Theater History syllabus or the Intro to Theater syllabus that’s entirely Western and this is what we want you to teach.” I became increasingly uncomfortable with what I was being asked to do, but I also didn’t have any power to make the substantive change that I was able to make here because, here, I was empowered to do so. Receiving a course release to redesign the class meant that I had time to reflect on the syllabus, but also to attend all the CITL (Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning) sessions and do the ACUE course on inclusive teaching. That really helped me conceptualize how to make the changes to reach these students today.

Ann van Dijk

I should also add that when I redesigned my unit so that it covered these three religious traditions equally, that it was eye-opening to me because my own education was almost entirely the Christian tradition of art in the Middle Ages. Once I started looking at these three religions in relation to each other, and I focused on particular types of artworks, manuscripts, sacred architecture and representations of God. I started looking at how these three different religions treated these three different types of visual expression in relation to each other, and it made me think about the material that I think of as my own territory in new and really interesting ways. That perspective of going outside of the tradition that you’re comfortable with and trying to look at it from the outside, from the point of view of these other traditions was extraordinarily healthy for me. I’m glad that I’m now teaching it to the students this way as well.

Gibson Cima

It’s paradoxical. You would think, to make this class more equitable, I will simplify it. But embracing the complexity of the subject is what makes it more inclusive because things are complex. To some degree, the way that I was taught was dumbed down. It was simplified and all those narratives were put in, like this happened and this happened, and this happened, this led inexorably to this. In fact, it could very easily have happened some other way. When we teach the students that complexity, it excites them.

Mary Quinlan

We did inherit parts of the course. For example, from Jeff Kowalski, who taught Africa and the Americas. We have incorporated our snapshots of those civilizations, showing how they coexisted at the same time and had brilliant cultures. But that’s obviousy not the same as 15 weeks to devote to the subject. It’s tough because there are so many cultures to teach and you do want to do it complexly, even though all you really can provide is a snapshot of what’s out there, and give studnets ideas on what future courses they might want to take in art history.

Gibson Cima

The other darling that I’ve had to kill is the idea of being completionist, or saying “here is all that you need to know to understand theater.” Instead, say, “Here is a tiny moment, here is a moment that I think opens up some really interesting questions about the nature of this subject.” Give up on, “well, they can’t possibly leave an intro to theater class without having read Hamlet or Oedipus Rex.” Instead, “What if they read these five other plays?” Or, maybe let’s not read any plays, let’s just look at the thing on stage.

Did you make any course policy changes to the syllabus? I made a number of changes to the policies in the syllabus that I think have been really, really helpful this semester.

I realized how many of my policies were punitive. “If you don’t come to class for three days or four days, then that’s a letter grade and on the fifth day you fail.” What happens when I give up on that and say, “It would be really great if you would attend class and I will incentivize coming to class, you get points for coming to class, but you don’t lose too many points for not coming to class.”

With late work, I used to say, “No late work, it’s due at the top of class in hard copy in my hands, that’s it.” Now I say, “I will accept late work up to two weeks after the assignment is due and there will be a letter grade penalty assessed.” That incentivizes turning it in on time, but it doesn’t ruin anyone who wanted to take more time. That has created a safety net for the class.

The more hope that I can continue to keep in the room, that they will be able to recover and can perform in the class, the better. Things chip away at that hope very quickly. Blackboard (NIU’s learning management system) has a nasty habit of sending my students emails, telling them that they’re failing or that they’ve missed this grade or that. When I look at it, they’ve missed one reading quiz, which is a percentage of a percentage of their grade, but they’re convinced that they’re failing because of it. So, part of that is trying to create policies that encourage students to come to class but don’t penalize them.

Ann van Dijk

One of the things I’ve found I really rethought is the concept of a test. What is a test for? Is a test to test what you know or is a test another opportunity to learn?

We had a problem with students frequently failing the test at the end of each unit and sometimes failing really miserably. I came up with an idea. I decided to try the notion of, what if you give students two chances at a test? They take the test and then they look at the test and they realize what they don’t know and then they can study what they don’t know and then they can retake the test and then they know it. A win-win situation rather than a cop-out.

Mary Quinlan

I think we do that in several ways because we also have weekly practice tests and they can take those. We all vary how many times we allow. I don’t want the students throwing darts at a dart board, so I allow two and in some cases three, but I don’t want them to have unlimited chances.

I have long been convinced, and I remember saying this when I was division head probably 15 years ago, that saying something one time isn’t teaching it. You have to repeat and you have to try to move it into different ways of saying it. Repetition from our weekly practice quizzes and then seeing the questions again, often in a slightly altered form on the unit test is repeating and learning something for the long haul, we hope. As Ann says, we’ve all gone to more than one, probably two attempts on the unit tests. And back to your point, Gibson, about late work, we also accept late work. You want to encourage them, incentivize their keeping up because you don’t want this tsunami at the end of the semester. But we also want them to learn the material, even if after the original deadline.

Gibson Cima

That’s where the two weeks comes in. I’m like, “Okay. Let’s move on. Those points are gone.”

Mary Quinlan

Back to the original question of how do we not just make it so easy that everyone gets an A and learns nothing? We cut back a little on the work because I had a leave and when we first came back, we started realizing, no, this is actually too many writing assignments. We do have a weekly quiz and some discussion or discussion plus writing at low stakes. That’s been helpful.

Gibson Cima

I think part of it is coming up against the work ethic that was ingrained into us as, “This isn’t going to work out in the real world. Deadlines are deadlines.” Then we get to the real world and we say, “I’m not going to have that chapter this month. Can you take it in July?”

Deadlines are fungible because they want the thing, you have the thing, you know how long it’s going to take for you to get it to where you can submit it. I love that idea of taking the exam and then taking it again because what is the point of just “gotcha, you didn’t pay attention to that one slide?”

I have a several creative assignments. I’ve turned from analyzing theater. Let’s just make theater and by making theater we start to understand how we might analyze it. I have reading quizzes to ensure that they’re doing the contextual reading because there is no exam.

I found that just asking them to read it wasn’t doing it. There is an incentive to do that reading, which is 10% of the overall grade. Blackboard is very helpful with these kinds of things. You can build out a lot of this in advance and it will run like an online class does. I’ve thought of it as an online class that meets in person, but there are lots of things that are happening online. It’s not fully hybrid, it’s not asynchronous, but it has a lot of those aspects to it.

Mary Quinlan

One thing we’re doing that you mentioned, Gibson, is being so selective. I used to explain to the classes, when a slide library existed in our building, there are 240,000 slides upstairs, we will be studying only the tiniest fraction of those. That was true, and it is still true in the digital age. So we are extremely selective. But the kinds of analytical work and skill-building that we do with them crosses a lot of art cultures–close visual analysist and clear descriptions of what is seen, for example.

We all teach in different modalities, too. What Ann does is asynchronous, I do synchronous and Helen does face-to-face. We all have our own ways of working with that.

Gibson Cima

My rule now is if they’re sitting, I’m losing and if they’re moving around then I’m winning. It’s still taught in a lecture hall, but I have the movement lab that’s right across the hall and I have that booked during the class. I can lecture very briefly, introduce a topic and then we can all move across the hall and we have to take our shoes off. It becomes this kind of entry into a playful space. There’s much more experiential learning happening. There are exercises, they are practically engaging in the making of theater. I had 60 students today, and they were all in the movement lab.

They got into six groups of 10, and they all pitched their plays to each other. They’ve all written plays, many of them the first play they’ve ever written in their life, probably the last play they’ll ever write. They were pitching their ideas to each other and deciding which play they were going to do. Then they had 15 minutes to rehearse it. Then we watched six new plays over the next 40 minutes. That was a very different experience about what it means to be a playwright and how to teach the idea of what a playwright is. The structure of the course has changed from a lecture-based, “I am the font of knowledge. You’ll receive that knowledge, then we will discuss it.” To, “I am here to guide you along this journey of you becoming a theater artist and then decide if that’s something that you enjoy doing.” So that’s been the major change.

Mary Quinlan

That’s wonderful. Are these all people who are theatre majors?

Gibson Cima

No, these are all non-majors. Gen ed students from the general population at NIU. All different majors, all different years, too because some seniors say, “I left these gen eds to the last possible second, I’m going to get them done.” I have freshmen and everybody in between and all different majors and they all just come together. That first class is really crucial because I have everybody in the movement room, and we just play. We play games that are not that different from games you would play at a five-year-old’s birthday party. They get the sense like, oh, this is one of those weird classes where we do silly things. From there I’m able to build on that.

Ann van Dijk

One thing we discarded from our course was a single major paper that used to be required. This is something I’ve been thinking about in a lot of my courses, which is that you’ve got what’s happening in the classroom and you’ve got students doing work related to what’s happening in the classroom. Then you throw this assignment at them that is not as integrated with what’s happening in the classroom, it’s just this extra thing that they must do. Unless you can convince yourself that what they must do for that assignment is crucial, doesn’t it make more sense to have as much as possible of what we’re asking them to do be closely integrated with what you’re teaching them in the course?

They still do a lot of writing in the class every week, but everything they’re writing about is directly related to what they’re being introduced to weekly in the material that’s being presented to them. They listen to short presentations about things, but it’s all directly related, or is presented in such a way that the relationship is clear.

On the one hand I made all these changes to introduce these three religious traditions and the art and architecture related to them. On the other hand, I was getting the feeling that it was somehow too distant from the lived experience of most of the students. How do I get them to understand that these art forms are in some ways still alive?

I found an artist who is the perfect illustration of this, a French Tunisian artist who does Islamic calligraphy, but he does it on walls in interesting settings and he calls it “calligraffiti.” So, I’m teaching them all about these very old traditions of manuscripts and the importance of different ways of writing in these sacred texts. Then I introduced them to this artist who’s writing on walls and asking them to think about the significance of the way writing looks. Writing’s not just something to be read, but it’s also something to be looked at. What is the significance of the visual appearance of writing? We see that playing out both in these very old manuscripts and in this contemporary artist’s work. My hope is, and the students do seem to respond to this assignment, that they like and they get the contemporary artist and that helps them think about this old stuff that they thought was just too far away from them in a new way.

Mary Quinlan

Each of the units now has examples of how the past art connects with present art. It’s that Faulkner quote, “The past isn’t dead, it’s not even past.”

Here is the project of eL Seed, the artist Ann mentioned. The students love this project and it’s because it is very interfaith, too. The image is part of Perception, a piece in Egypt, spread across a number of buildings in a Coptic Christian neighborhood. The Coptic Christians are the garbage pickers of Cairo, and suffer stigma because of this. But, eL Seed has but he’s combined so many different things: the meaning of the words he painted, the bright colors (including the use of glow-in-the-dark paint) and the fact that to see the entire image, you have to go to a certain place, shift your perspective so to speak.

Then in my unit, when I show the Renaissance equestrian monuments, I have used them to examine Confederate equestrian monuments and how they related to slavery in the United States, what equestrian monuments did for their audiences in the past, and what equestrian monuments do now–similarities and differences.

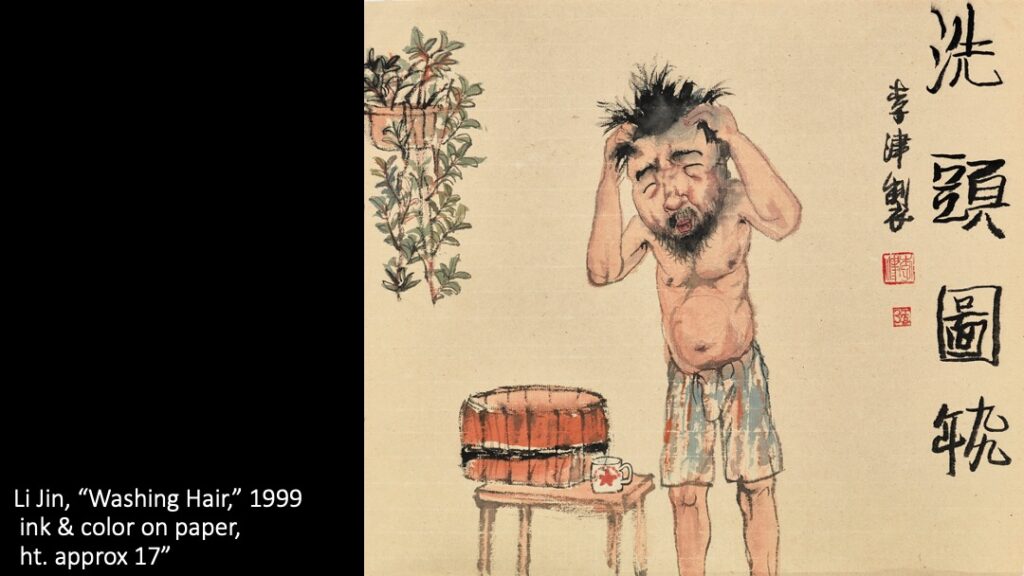

With Helen’s unit on Asian art, she introduces the questions of how an artist today can visually communicate political messages in Communist China without getting imprisoned or killed? She’s bringing in the ancient Chinese ink painting tradition and studets examine how the artist is still using it, and how the political messages are similar or different from those in the ancient tradition. here’s a lot at stake, but she’s bringing in the ancient Chinese ink painting tradition and using it in this way. Because I’m doing the synchronous, I can frequently ask the students to relate these things to a more present moment.

Gibson Cima

It’s difficult to tell why students withdraw or fail a class.The truth is they withdraw from any number of reasons, personal reasons. They find another class that they like, they fail for any number of reasons. I have tried to build a syllabus where if a student completes their assignments, they are not being penalized such that they would fail the class by not being able to attend a session.

The other intervention has been making content that reflects the students that are present in the room. Rather than some of the content in the courses that I used to take that told people of color that their cultures were not as important as White culture and that’s awful and wrong, and I don’t want to perpetuate that in my classroom.

Mary Quinlan

We have a fabulous undergraduate advisor (Bethany Geiseman) and a team of them. I incentivize, I think we all incentivize, by giving points each class so I can see who hasn’t been at three classes and then I send that person an email cc’ing Bethany saying, “Let me know what I can do.” The answers are charming oftentimes. They’re 18 and come out of some of the worst educational systems where they just got robbed. I had a student who asked, “What am I missing?” And I’m like, “Oh.” Because he didn’t really know how to use Blackboard well enough. Sometimes it’s the simplest things, but you must catch them right away. You must catch them after three classes and send that email because otherwise then they’re just drowning.

Ann van Dijk

With the smaller groups and because I’m teaching the asynchronous students, I’ve also felt that I need to do more of the grading, rather than handing it all to a teaching assistant. I’m getting to know my students better because I’m reading more of their work.

Mary Quinlan

And when you grade their work, you learn their personalities, I think, which is really lovely.

Gibson Cima

It’s been wonderful to put so much of what I have been learning in these sessions into practice and to say, “Okay, this represents what is the current best practices in teaching,” and I’m going to try to do that. So much of what I was taught, I know my Shakespeare, I could discourse at length on him. I can quote you chapter and verse from those plays and Ibsen and all of it. But I find that that is not what is connecting to the students. What’s connecting to the students is saying, “Here are the structural problems with the way I was taught this the assumptions underlying that, and I’m going to teach it to you differently and here is how I am offering that to you.” It’s an exciting opportunity to reshape the narrative and break the wheel. And I’m loving it.

The students that excel do things I never would’ve thought of with the assignment.

Mary Quinlan

I agree. I love these intro course students.