Gibson Cima is assistant professor of theater history and head of theatre studies in the NIU School of Theatre and Dance. For several years he has traveled to South Africa to study and research South African Theatre. Cima is presenting the lecture, Future Nostalgias” focused on South African anti-apartheid protest theatre on the post-apartheid stage, Thursday, October 10 at 5:10 p.m. at the NIU Art Museum in Altgeld Hall room 125.

Cima talked to the NIU Arts Blog about his three-week research trip to South Africa this past summer.

Gibson Cima, assistant professor of theater history and head of theater studies

I’ve been studying South African theatre since 2006 when I first went visited the country to research Athol Fugard. Fugard is a white South African playwright who collaborated with black actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona during apartheid under very difficult circumstances when it was illegal for them to be in the same room together. Despite these constraints, they made theatre that traveled all over the world and raised awareness about the terrible situation in South Africa under apartheid, a legally sanctioned system of racial oppression that existed from 1948 to 1994.

When I first travelled to South Africa, I saw an original-cast revival Sizwe Banzi is Dead, which is a famous South African protest play written by Fugard, Kani, and Ntshona. Kani and Ntshona played the roles that they originated. I sat in the audience thinking, “What does this play have to say to this contemporary South African audience?” It’s protest theatre protesting something that’s been officially over for twelve years at that point. Yet it was still speaking to that audience because though apartheid was legally dismantled in 1994, its effects are ongoing. How the anti-apartheid protest theatre continues to influence the post-apartheid stage became the central question that sustains my research. I’m now working on a book based on my research that is tentatively titled “Future Nostalgias: South African Anti-Apartheid Theater on Post-Apartheid Stages.”

I have been traveling back and forth to South Africa for many years, and I lived and worked there for a year. In 2013, I had a postdoctoral fellowship at Tshwane University of Technology (TUT) in Pretoria. Prior to this recent trip, however, I hadn’t been to South Africa since 2015 and so it was really exciting to be able to visit the archives where I’m conducting research for my book and to attend the National Arts Festival (NAF).

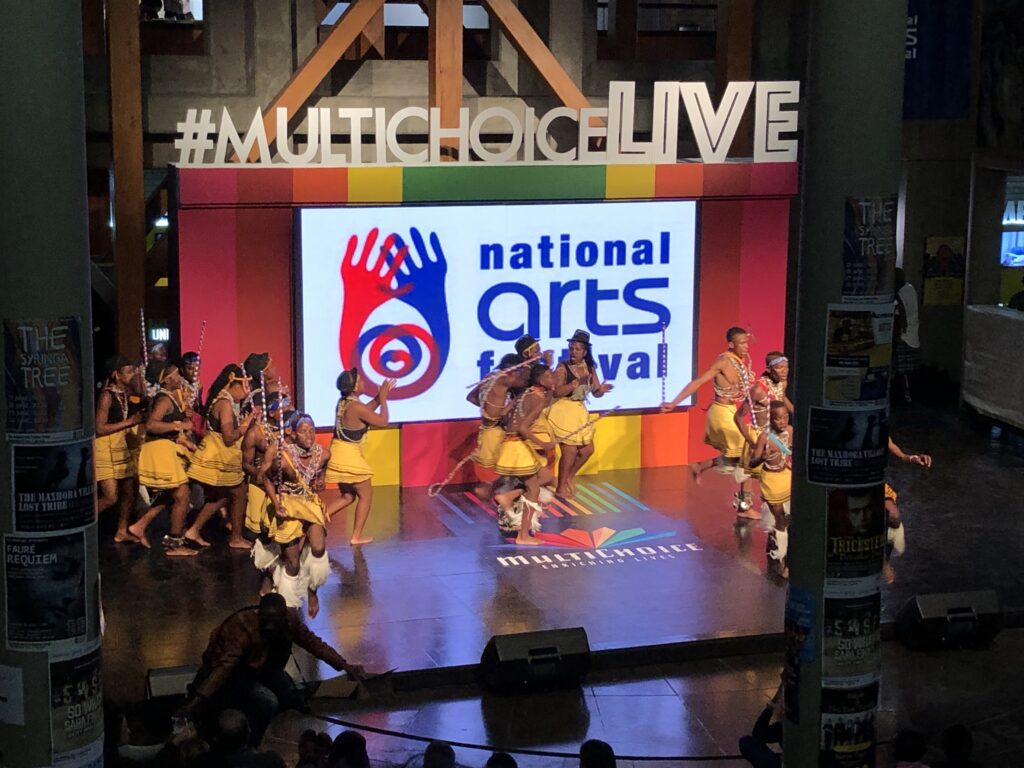

The NAF is one of the largest arts festivals in the world. It’s held in a tiny little town, which used to be called Grahamstown, but has recently been renamed Makhanda. That gives some sense of the enormous change that has happened in that country as they replaced the colonial names of places with native names. That change is visible at the festival. It was palpable because this is a festival where the absolute best South African theatre artists gather to show new work. Normally that means a group of about five or ten famous theatre artists showcasing their new work. But at this festival only one of those ten or so well-known theatre makers brought new work to the stage.

Instead, there was an entirely new crop of incredibly talented young theatre practitioners who are colloquially known as “Born Frees.” These are people born after 1994 when apartheid was no longer legally sanctioned. They’re now in their mid-twenties, but they reject that label of being “born free” and they are saying, “We have been sold a raw deal. We’ve been told that we grew up in the Rainbow Nation.” The Rainbow Nation is a concept credited to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, that Nelson Mandela quoted in his inaugural address in 1994. Mandela said, “You are the Rainbow People of God.” That became a narrative about South Africa–that it was a non-racist, nonsexist, democratic utopia–which they feel is not the case.

What was really exciting for me at the festival was to see an entirely new generation of South Africans presenting their own work at the newly renamed festival. When I was teaching it at TUT in 2013, one of my students said, “We’re really sick and tired of doing, Woza Albert!,” the famous South African protest play. “But when we do our own work, nobody comes.”

They were producing these famous plays because they had name recognition, but now that seems to have shifted at the festival. They are themselves a theatrical public and they’re attending each other’s work. It’s fascinating that a festival that was designed, in 1974, to promote English in South Africa is now a very multi-lingual, multi-cultural festival where artists are focused on presenting work about their own lived experiences. In my own history of attending this festival over the past thirteen years, there would be shows on the main stage that would have some native language in them, but it would be largely in English.

Now we’re starting to see performances that are almost entirely in Xhosa or entirely in Zulu and have just a few words of English to help those, like me, who don’t understand those languages, so we can follow along. It was really exciting to see a new generation of South Africans taking on the mantle of protest theatre.

I interviewed the famous South African protest actor, John Kani [best known to American movie audiences as T’Chaka, the father of Black Panther in the Marvel Cinematic Universe], and he said, “When Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, it canceled every ‘Free Mandela’ play in the world, immediately.”

Protest theatre is a difficult business, but a business nonetheless. All the theatre critics went to the funeral of protest theatre and didn’t invite the artists who created that body of work. They came back and said, “Now you have to do theatre for art’s sake.” But they had no idea what that was. There was an initial celebration of a unity and democracy that then quickly curdled.

South Africa and the U.S. are often compared to one another because they both have these terribly racist pasts. However, South Africa has had a truth and reconciliation commission, which has begun in some way to deal with its past. When the African National Congress (ANC) took power in 1994, they said things like, “a refrigerator for every family, clean water, access to education, access to medical attention.” Those promises have not been realized and it’s twenty-five years later. There is a huge group of disenfranchised young people in South Africa that are getting angrier and angrier. One of the avenues they’re turning to now is protest theatre.

When you turn to protest theatre, what models are you using? They’re using the anti-apartheid theatre models. I saw a play at the festival that was called Currently Gold and it recalled Woza Albert!, but instead of two actors, it had four actors. It used that same vaudeville structure where they’re playing multiple characters and using found objects, tires and umbrellas and coats and things to create objects doing satire.

Woza Albert! satirized the National Party and the apartheid government. Currently Gold satirizes the ANC and the twenty-five years of South African democracy. And it wasn’t the only show at the festival this year that resembled Woza Albert!. This supports my thesis about what happens to protest theatre when the thing that it is ostensibly protesting has ended. What I am finding is the struggle continues, and it continues in revivals of protest theatre. Sometimes in original cast revivals and sometimes in new productions that are reviving these old protest models to speak to present concerns–to demonstrate the distance they’ve traveled, and the distance that they still need to go.

In these protest plays I find a longing for the future, homesickness for an imagined future. That’s what I call a future nostalgia. When they are revived, we see the distance between the imagined future of the past and the present reality. It’s an idea that can be applied to Czech theatre, to Russian theatre, to American theatre. I am examining what happens in any post-revolutionary theatrical community.

It has been fascinating to see the kind of theatre that has been produced in South Africa over the past thirteen years, some of which was still dealing with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its aftermath. Some of it was starting to articulate a new South African black identity that had not been articulated before in traditionally white spaces like the State Theatre, which is a sort of like the Kennedy Center in the US, now being run and programmed by black people. I’ve been a witness to significant changes as I’ve studied South African theatre. This trip was another piece in that puzzle to be able to go back, touch base, reconnect with many of my friends and the subjects of my research and get to visit the Amazwi South African Museum of African Literature, which used to be called the National English Literary Museum when I started this work. I was able to go into the archives and start to see a little bit about the history of the National Arts Festival.

It was an incredible trip. Nineteen days of fascinating engagement with post-apartheid South African theatre.