A series of coincidences led NIU Associate Professor of Music Jui-Ching Wang to Indonesia to witness firsthand the value of traditional children’s singing games.

NIU Associate Professor Jui-Ching Wang

At the beginning of her tenure in NIU’s School of Music, Wang found herself directing the school’s Indonesian Gamelan Ensemble. To do the best job possible she immersed herself in learning everything she could about gamelan, a traditional Indonesian percussion ensemble.

“[NIU’s] Founders Memorial Library has a special collection on the fourth floor,” Wang said. “It has Southeast Asian artifacts, and books, and I was able to learn some songs from the book so that I could teach them. It really helped me become more comfortable, and then, one day I found some song books that had children’s singing games in them.”

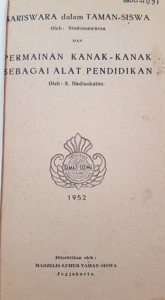

At the same time, Wang had enrolled in a course at NIU to learn to speak and write Indonesian. She just happened to have a Fulbright Foreign Language Teaching Assistant in the class named Dyah Pandam Mitayani, or “Mita.” Mita was interested in Wang’s musical background as she herself came from a musical family. As coincidence would have it, Mita’s grandfather, S. Hadisukatno had written a book on integrating traditional singing games into school curriculum, and that book was also available in the NIU library.

Book on traditional Indonesian singing games written by Mita’s grandfather.

“Mita told me the whole story of how her grandfather composed children’s songs based on the traditional music style in Indonesia,” Wang said. “On the [Indonesian] Island of Java there’s an elementary school that was established in 1922 and it was the first school for Javanese children to attend.”

The school named Taman Siswa, which translates to “Children’s Garden.”

“Java was colonized by the Dutch,” Wang continued. “Prior to this school opening, only members of the royal family or noble class could go to school with the Dutch. So ordinary Javanese children didn’t go to school.”

“The founder of that school had met Montessori when he was an exile in the Netherlands in the 1910s, and he was influenced by Montessori. So when he came back to Java he worked to incorporate their unique cultural heritage into the school. He felt that the European education system was good, but he wanted Indonesians to value their own cultural heritage. So he insisted that among the traditional values that were being taught, that singing games be incorporated into the curriculum.”

“Before that, children would just sing and play outside, and help their parents with farming or house chores. But all along they would play together and a group and that’s how the singing games started.”

Singing games went from the primary way Indonesian children learned to being intertwined with a European system of learning, giving these young students the best of both worlds, and taking best advantage of what Wang says is an innate gift for multi-tasking.

“There’s a strong musical characteristic there,” she said. “It’s fascinating how young children can do multiple layers of singing, and play instruments. One group of children can play instruments and the other group can sing against what they play. They do it without having formal music training. What attracted me to learning more and more about it was how complex the music is. The more I learned the Indonesian language, the more I learned about the history of Indonesia and began to realize that the language and music is really a whole package that comes together.”

In 2014, Wang traveled to visit Mita’s family in Yogakarta on the Island of Java for ten days.

“Her parents were very enthusiastic about my visit, and took me to Taman Siswa, where I was greeted by a group of young children,” Wang said. “They sang and danced and that’s what really got me interested in studying how, in the 21st century, there are still some schools who are interested in, and value this kind of learning.”

Wang says that even in Indonesia this kind of curriculum is rare. “It’s more like here where we don’t allocate time for children to learn that kind of tradition. It takes a lot to do that.”

Upon her return Wang published an article about the use of singing games in Indonesian schools. In 2016, she earned a Fulbright Scholarship to return to Java to continue her research.

She spent ten months visiting that same elementary school nearly every day.

“In my proposal I specified that Taman Siswa was where I wanted to go for my Fulbright for two reasons,” she said. “The first is that they are still teaching using singing games, unlike many of the other schools in Indonesia. The other schools feel like, ‘It’s too much a waste of time. We don’t care about our traditional culture, we just want to catch up with the modern world.’ The second reason is that the school has a museum right on the campus. The museum houses all of the writings of the founder of the school, Ki Hadjar Dewantara. Not only did he found the school, but after the country got its independence he became their first minister of education. He’s a very important person in their history, but he didn’t enjoy politics. As soon as he got their education system set up he stepped down. He wrote a lot of books and published a magazine about their education methods. So I could do all of my research there, while also studying what the school is doing to counteract the modern trend of education.”

“Why is it important to have children play inside of a school setting?” Wang asked. “Because they don’t want children to be just sitting in a classroom, receiving information. They want children to grow in a natural setting. That’s why they named the school ‘Children’s Garden,’ because every child is going to grow differently, just like you have in your garden. Different flowers, different trees, different everything. It’s child-centered learning.”

Wang said that despite the importance that the Taman Siswa movement had in the development of Indonesian education, it is dying out.

“When the school system started there were hundreds of schools in different branches,” she said. “Now, there are only about 120 schools left. There’s a centralized educational system in Indonesia, and the reason Taman Siswa has their own curriculum is because the founder refused to receive funding from the government, so it’s being operated using its own sources of funding.”

“When the school system started there were hundreds of schools in different branches,” she said. “Now, there are only about 120 schools left. There’s a centralized educational system in Indonesia, and the reason Taman Siswa has their own curriculum is because the founder refused to receive funding from the government, so it’s being operated using its own sources of funding.”

When it was founded, Taman Siswa’s curriculum was completely unique. Nearly 100 years later, the circle is nearly complete and it is once again unique, and that, Wang said, is an opportunity.

“They feel like they have a chance to revive what was glorious in the past,” she said. “They see this as the pearl now. They have something that other schools don’t have, and that was the reason they valued my time there.”

With Wang’s assistance, they submitted a proposal to the International Society for Music Education World Conference, which this year will be held in Azerbaijan. The proposal was accepted and a group of children from Taman Siswa will perform.

“They are very excited,” Wang said. “It’s going to be the first time ever that an Indonesian children’s group will perform these kinds of traditional songs outside of Indonesia”

She is putting what she learned to use, incorporating her findings and methods into the elementary education and general music method courses that she teaches at NIU. She has also developed graduate level and seminar courses, and is always looking for ways to lead groups of graduate students and collaborate with them or faculty to develop research projects together.

One such project is a collaboration with Yogyakarta State University in Yogyakart to conduct a survey examining how non-Taman Siswa public schools in central Java incorporate the use of some singing games into their curricula.

“I hope to be able to go visit and get more data from other school systems, so that I can look at it from a broader perspective,” Wang said.

As if that work isn’t keeping her busy enough, upon returning from Indonesia, Wang was offered the chance to also serve as the Acting Assistant Director of NIU’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

“It’s a very interesting job,” she said. “I oversee several important scholarship programs and I work as an advisor for students who have a concentration in Southeast Asian Studies. I’m also involved in outreach opportunities for travel to different parts of the world. It’s pretty exciting.”